It wasn’t until high school when I understood how important strength and conditioning was to improving ski performance. My interest grew from frustration with middling competitive results. Having believed that physical fitness improved the probability of athletic success I set out to be in better “ski shape”. I wanted to gauge how my physical fitness compared to other skiers, and what it would take to physically stand above the rest of the competition. Unfortunately, I never learned of such a barometer. Now, at the intersection of my passion for skiing and physical therapy research, I’ve started to finally learn what I was searching for 15 years ago. And I want to share it with NS. This article aims to: to help skiers measure their physical fitness compared to their age-related skiing peers, identify which physical fitness tests are an injury risk factor, and free tips on how to reduce injury risk so you don’t miss time away from the sport.

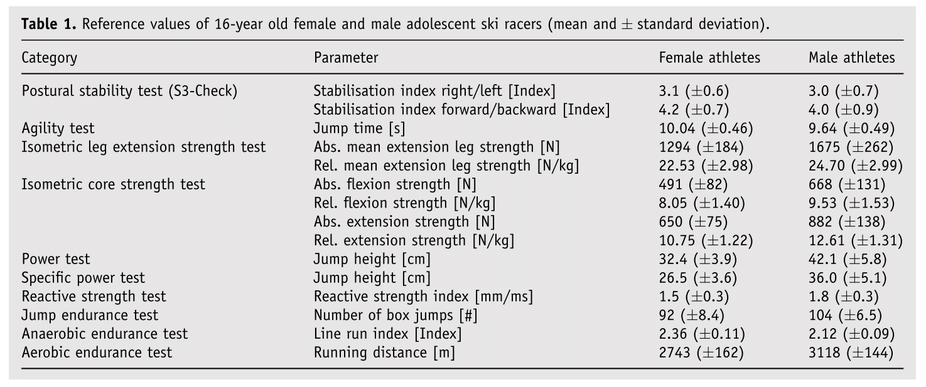

Elite skiing performance partially results from goal-oriented training programs that are derived from identifying and evaluating the physical fitness of a skier beginning at youth. Large organizational skiing bodies, such as the Austrian Ski Federation, have investigated the physical fitness of their skiers starting at a young age so they can know how to train the musculoskeletal system to meet the demands of skiing. Below are the reference values following a battery of physical fitness tests performed by 16 year old female and male adolescent ski racers a part of the country’s talent development program.

Pay most attention to the agility test, power test, specific power test, reactive strength test, jump endurance test, anaerobic endurance test, and aerobic endurance test because these are tests you can easily perform and analyze yourself. The units of measurement are in brackets underneath the parameter column. For example, the average youth female skier completed the agility test in 10.04 seconds and the average youth male skier completed the same test in 9.64 seconds. As another example, youth female skiers jumped on average a height of 32.4 centimeters during the power test, and youth male skiers jumped on average a height of 42.1 centimeters during the same test. You can learn how each test is performed by reading the description below and referencing the article itself (page 3).

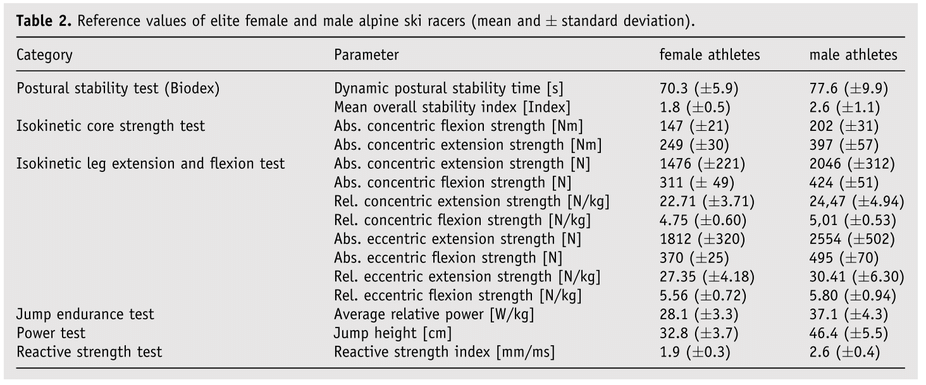

The jump from youth skier to elite skier poses large challenges including the high intensity and volume of training required to become “elite” and then maintaining elite level performance for a long period of time. Dr. Jim Taylor, renowned skier psychologist refers to this continued length of success as finding your “prime” skiing performance, instead of the commonly used term “peak” performance. The latter term implies only a short period of time on top with a sharp drop off. A skier requires approximately 10 years of preparation to compete at an elite international level. While excellent physical preparation is crucial for young skiers it is no guarantee of athletic success. However, it’s important to focus on the areas that skiers are capable of modifying, and training is a large one. If you are looking to make that jump to “elite” then take a look at the reference values for elite female and male ski racers from the Austrian olympic team who are greater than 20 years of age.

1 Repetition Squat (Kilograms)

Spanish Junior Development Team: 49

Spanish Junior Development Team: 69

Hex Test (seconds)

USA National A and B Team: 29.68

USA National A and B Teams:29.05

90-s 40-cm Lateral Box Jump Test (#of jumps)

USA National A and B Teams: 79

USA National A and B Teams: 97

V02 Max (mL/kg x min)

Austrian National Team: 59.5

Austrian National Team: 56.9

Lactate Threshold (W/kg)

Austrian National Team: 2.9

Austrian National Team: 3.4

These batteries of tests have been further investigated by researchers to determine which ones can serve as predictive risk factors for skiing injuries. The tests that assess symmetrical core and reactive strength (during the drop jump vertical test) are significant injury risk factors in youth alpine skiing. Symmetric core strength-the ratio of core strength between the trunk flexors (i.e. located in the front of the body) and the trunk extensors (i.e. located in the back of the body) should be equal. However, male skiers who suffered an ACL injury demonstrated stronger trunk flexor muscles and/or weaker trunk extensor muscles. Imbalanced core strength makes it difficult for the skier to control his or her trunk during expected or unexpected changes in body positioning that can lead to the knee being in a vulnerable position where ACL tears commonly occur. Reactive strength is assessed during the drop jump vertical and is measured as the amount of time from landing to leaving the ground (i.e. amount of time spent in contact with the ground). Skiers who spent more time in contact with the ground during the transition were at a higher injury risk and were also found to have their knee in that same dangerous position where ACL injuries commonly occur.

Here are some helpful tips on how to address reactive and core strength deficits to reduce the risk of skiing related injuries. The core muscles responsible for extending the trunk include the lumbar paraspinals, multifidus, and quadratus lumborum and each can best be activated performing single leg bridging, side planks, single arm suitcase carry, GHD oblique holds and bird dog rows. Enhanced reactive strength (i.e. less time spent in contact with the ground between landing and takeoff) is predominantly driven by improved braking (landing/planting) as opposed to improved propulsion (take off). Focusing on deceleration and eccentric work is highly important in the context of reactive strength development, but don’t discount propulsive performance. Just know that more is gained from learning how to brake better. A practical exercise is taking the test and turning it into an exercise by performing eccentric drop squats.

Hope this information serves you well. Thanks!

Dr. Benjamin Pierce Costa, PT, DPT

Telephysio PT-Owner

US Ski Team Rotational Physical Therapist

References

Muller L, Hildenbrandt C, Muller E, Fink C, Raschnr C. Long-term athletic development on youth alpine ski racing: the effect of physical fitness, ski racing technique, anthropometrics and biological maturity status on injuries. Front Physiol. 2017;8(656):1-11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2017.00656

Hydren JR, Volek JS, Mareh CM, Comstock BA, Kraemer WJ. Review of strength and conditioning for alpine ski racing. 2013. Strength Cond J; 35(1): 10-28. https://journals.lww.com/nsca-scj

Raschner C, Platzer HP, Patterson C, Werner I, Huber R, Hildenbrandt C. The relationship between ACL injuries and physical fitness in young competitive ski racers: A 10-year longitudinal study. Br J Sports Med. 2012;46:1065-1071. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2012-091050.

Raschner C, Muller L, Patterson C, Platzer HP, Ebenbichler C, Luchner R et al. Current performance testing trends in junior and elite Austrian alpine ski, snowboard, and ski cross racers. Sport Orthop Traumatol. 2013;29:193-202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orthtr.2013.07.016

Schmitt KU, Horterer N, Vogt M, Frey WO, Lorenzetti S. Investigating physical fitness and race performance as determinants for the ACL injury risk in Alpine ski racing. BMC Sports Sci Md R. 2016;8(23):1-9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13102-016-0049-6.

Douglas J, Pearson S, Ross A, McGuigan M. Kinetic determinants of reactive strength in highly trained sprint athletes. The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2017;32(6):1562-1570. https://doi.org/10.1519/jsc.0000000000002245.

Neumayr G, Hoertnagl H, Pfister R, Koller A, Eibl G, Raas E. Physical and physiological factors associated with success in professional alpine skiing, Int J Sports Med. 2003;24:571-575

Reid RC and Johnson SC. Validation of sport specific field tests for elite and developing alpine ski racers. In Science and Skiing, vol I. New York, NY: Meyer and Meyer Sport (UK) Ltd., 1997. Pp. 284-296.

Emeterio CA and Gonzalez-Badillo JJ. The physical and athropometric profiles of adolescent alpine skiers and their relationship with sporting rank. J Strength Cond Res. 2011:24:1007-1012.

McGill S. Core training: Evidence translating to better performance and injury prevention. Strength Cond J. 2010;32:33-46.

Ekstrom RA, Donatelli RA, Carp KC. Electromyographic analysis of core trunk, hip, and thigh muscles during 9 rehabilitation exercises. J Orthop Sports Phys. 2007;37(12): 754-762.

Comments