‘Tis the season for depressing old winter safety Cy to come out of the cave and wave my bony fingers at all these skiers having too much fun. It’s outreach season for our local SAR team, it’s “fat snowpack, let's make sketchy choices” season in much of the mountain west, and this stuff is on my mind, so here we go!

For most skiers, we’re focused on our goals, with the prospect of needing a rescue usually taking a hazy backseat. We do everything we can to make sure we’re successful, and if we’re not, we figure we can call 911, they’ll send a helicopter, and we’ll be sheepish as they whisk us off the hill. Unfortunately, it’s a little trickier than that. So here’s what I’ve picked up after four years of volunteering on our local SAR team, as well as a couple of incidents that I was on the other end of. This article is most relevant for skiers in the United States, where SAR teams are organized by county, so there will be some small differences for folks from Canada and Europe, but the guiding principles will be similar.

How not to get rescued

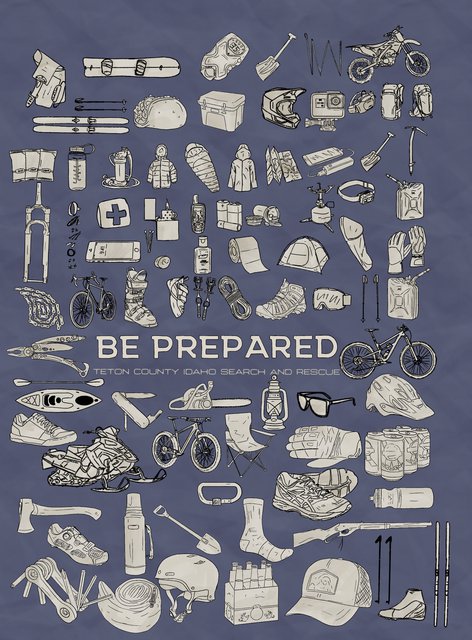

We might as well start with the obvious: ski days are better when you get home under your own power, and don’t need to call for help. So be prepared, make sure you’ve got the gear, information, and experience needed to safely accomplish your objectives. There are plenty of wonderful resources available both online and in real life to help you avoid needing a rescue. But sometimes, accidents happen, and there’s nothing we can do ahead of time to forestall them. So, here’s what to do when things go sideways.

Leave a plan

Make a plan, leave a plan. When figuring out your ski goals for the day, come up with a quick outline: Where are you going? Where are you parking? Who are you going with? When should you be home? When should someone call for help if you’re not home? Leave this with someone responsible, with explicit instructions for the hierarchy of folks to contact. For example: “If you don’t hear from me by nine, call Bob, I’ll be with him, and my phone might die, if you don’t hear back from him by ten, call 911.” Leaving that information is important because it helps make sure that:

If you’re gonna need help, do your best to make sure it’s a rescue and not a search

This one isn’t super obvious because we throw around those terms like they’re synonyms, and they’re not. Searches and rescues are two different things. And, generally, searches suck way more for everyone involved. Searches are conducted when someone is missing. Rescues are conducted when first responders know where you are, but you’re in trouble. Searches often take days, and it takes a long time to assemble the resources needed for them. They require more manpower, K9’s, and other assets. And because they’re vague, because by definition, first responders don’t have the most crucial information, they're at higher risk.

So teams are less likely to conduct a search at night, or in bad weather, or in dangerous avy conditions than they are to conduct a rescue. If they know right where you are, it takes less resources, and less risk to help you than it does to try to find you.

Know where you are

The number one way to make sure your emergency proceeds as a rescue and not a missing person search is to know where you are, and have a way to communicate that to first responders. Knowing where you are is relatively easy. Any mapping app will give you a lat/long, or the compass app on your phone should also give you that information. Communicating it is more difficult. An InReach or similar satellite messaging device goes a long way towards making sure you’re always connected. The new Iphone also has this capability, but it’s unclear how good their satellite coverage is right now.

But, you’re cheap, you don’t want to shell out for an InReach, I get it. I don’t own one either. This is no replacement for a satellite communicator, but it’s better than nothing: Use the mapping app of your choice to game out phone service. Most popular mapping apps have an overlay for phone service, from different providers. You can either check ahead of time, or download this layer to the map you’re using. In a lot of areas, there’s pretty good service in the backcountry, and having that map downloaded gives you an idea of the closest place with coverage. Often you just need to climb a ridge or go down the drainage a little further to get coverage. Using those overlays will give you that info. And, it’s important to note, texts will often go through when there isn’t enough service for a call.

On that note: your phone is an incredibly valuable tool. Keep it charged, bring a battery bank, pick a mapping app (they’re all pretty good these days) and pay for it, and learn how to use it. Learn how to download maps to use in airplane mode, and use them. They’ll help rescuers and will help you avoid needing to call rescuers. BUT, don’t expect dispatch to know exactly where you are, based on some vague idea of surveillance tech. Sometimes they can figure that out, but it’s a lot easier for everyone if you just give them your coordinates.

The Backcountry SOS app is a great resource that helps get rescuers your info, or you can text 911 with info from your mapping app.

Call with a plan

Calling 911 isn’t a trivial matter. So have a plan before you call or text 911. Distill the essential information so that if you get cut off or run out of battery or whatever, the important info can still get through. The barest bones are location and issue. “Broken leg at xxxx coordinate” is enough to get a response moving, and is a lot more useful than “we left this trailhead and skinned this and then skied this and the skiing was sick, but Bobby crashed and at first we weren’t sure what was happening, but now we think he’s broken his leg but anyway it’s getting dark and we might be able to get home but we might not, ya know?”

Understand where your call goes

Unless you’re having issues inside a ski resort, call 911, not patrol of the closest resort, or the number your local SAR team has listed on their website. In the US most SAR teams are part of the county, so they need to be activated by the county’s 911 dispatcher. When you call 911, a combination of factors affect where your call actually goes. Ideally, it goes to the county dispatcher for the county you’re in. But, as an example, I’m on Teton County Idaho SAR, but we’re right next to Teton County Wyoming SAR, and sometimes, 911 calls from Wyoming get routed to our Idaho dispatch. So, knowing your exact coordinates will help the dispatcher you reach initially determine where to route your call. This summer I called 911 from Wyoming, was initially connected to Idaho dispatch, and then they connected me to Wyoming dispatch. Knowing what county you’re actually in can help speed up this process.

The 911 dispatcher will then get preliminary details from you, and use those to decide what resources to call out. If that dispatcher decides to call out SAR, you’ll probably get another call, from someone on Search and Rescue, looking for more info to inform their response. So…

Pick up your damn phone

If you are having a bad time in the mountains, and someone calls you, they’re probably trying to help you. Answer your phone. Even if you haven’t called 911 yet, maybe someone at home did, and gave first responders your number. Pick up your phone. Talk to whoever is calling you. Answer their questions. Even if you’re already answered those same questions. This interview is very important. Your info might be passed off to another person on the team, or another organization, and they may need to contact you. Don’t ignore unknown numbers.

Have a realistic timeline

This is one of the biggest things that sunk in for me after some time on SAR. It takes a while to get a rescue moving. Sometimes we just imagine that there’s a bunch of qualified people waiting around, geared up, ready to jump on a helicopter and save you. And sure, sometimes that’s true. But it’s not always the case. Locally, your call goes to dispatch, they decide to alert SAR advisors, we discuss the details, and decide to call out the team. The team is just a bunch of regular folks, going about our jobs, raising kids, commuting, skiing for pleasure, living our lives. So, sometimes we’ll have folks geared up and ready in 15 minutes. Other times, it can take hours to get a team together. That’s just the reality of being on a volunteer SAR team.

And then, once that team is ready, they still have to get to you. Hook up the trailers, drive 20 miles on shitty, icy roads at night, unload the sleds, load up the evacuation rig, sled in 12 miles of whooped out trail and challenging terrain, then, maybe we can help you.

Sure, sometimes it’s sunny and calm and the helicopter can whisk you out. But usually, when things go wrong, the weather isn’t great. So budget the time it took you to get where you are, plus at least an hour.

Call 911 before you absolutely need it, get help moving before things get dire.

It’s not over when you make contact with rescuers

There’s a pretty common theme when folks finally make contact with rescuers, they experience relief, and a feeling of surrender. Before I was on SAR, I sort of felt the same way little kids feel about their parents, “once they’re here they’ll deal with the emergency immediately, and I’ll be safe.” But SAR teams aren’t your mom, and they can’t fix everything with a kiss. So be prepared to help them help you. Often, SAR teams around here are responding to folks who are stuck. Skiers or snowmobilers who went down something they can’t get back up. But, if that’s you, you’re still going to have to hike back up. Usually rescuers will bring snowshoes for you, they’ll help you put them on, and hike to somewhere where mechanized transport can reach you. So, if you’re cliffed out, after exiting a ski resort, you’re going to have to walk back up, one way or another. And the more you can climb before rescuers reach you, the better off you’ll be when they do.

Conclusion

Any day in the mountains that goes badly enough that you need to call for help is, by definition, a jarring, disorienting, traumatic experience. And, if you’ve never thought about what actually happens when you do call for help, and aren’t ready for that process, that discomfort will only be amplified. So, it’s a good idea to game out in your head what potential rescues might actually look like, and how you’d facilitate them.

Comments