If the proliferation of “what backcountry bindings should I buy” threads in Gear Talk is any indication, ‘tis the season for Newschoolers to shop for new bindings. And, while there are plenty of pay-to-play gear guides on the internet, as well as some more objective outlets recommending gear based on merit, there’s not as much information catering to the specific needs of us jibby, jumpy, backwards-skiing folks. So, here’s an overview of the current backcountry binding landscape.

A note on the recommendations: I don’t have any sponsors. Nobody is paying me to say nice things about their gear, or even giving me that gear for free. I have personal relationships with folks at a few indy brands, and I’m lucky enough to get discounts on some gear. But this is about as unbiased a breakdown as possible.

The Three Headed Dog

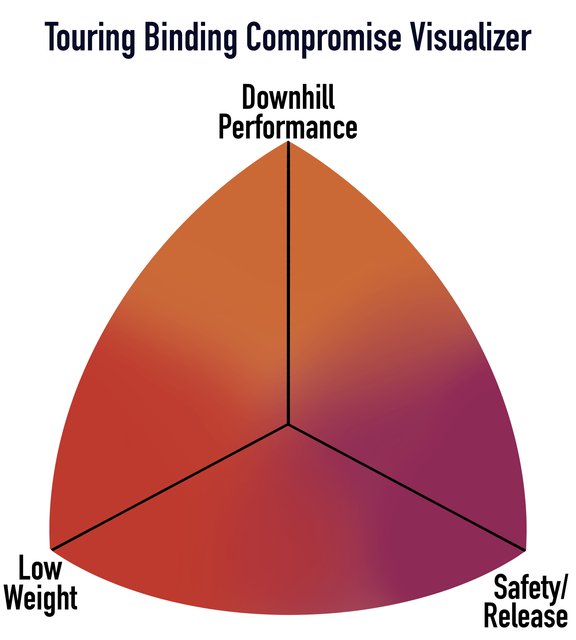

Before we get down to specific gear that’s great for new school skiers who like walking uphill, it’s helpful to understand the theory behind shopping for new backcountry skiing gear. I’ve found that it’s often easiest to think of every gear choice as the cumulation of a series of compromises. If you can build a logical path to winnow down all the options, it’s much simpler to find gear that works well for you as a skier. In mountain biking, the adage is “strong, light, cheap, pick two.” In skiing though, it’s a little more complicated. There’s a different set of goals for each part of your gear equation, and from there, each piece of gear needs to interact logically with the rest of your kit.

I think that the best way to think about touring bindings if you’re a skier who likes to walk uphill and jump off things is in terms of weight, safety, and performance. And where you fall on that spectrum is different for every skier.

Safety is the hardest category to define. In broad terms, bindings are "safe" when they come off your boots before you tear a knee or break a bone, but stay on when you're charging in consequential terrain. They help you avoid blowing ligaments or falling to your death.

Don't read this part unless you're a nerd.

But, it's hard to come up with a universal standard for safety to judge such dissimilar bindings on. So in this piece, we're using bindings that meet the ISO 9462 release standard (the same standard that alpine bindings must meet) as the bar for safety. Of course, skiers still blow their knees in alpine bindings all the time. And some skiers have opinions about safety within that standard, many folks perceive Pivots as being "safer" than Griffons. So it's an imperfect standard. But it's the highest standard we currently have.

Some of these bindings do not meet the ISO 9462 standard, but do meet the DIN ISO 13992 Alpine Touring standard. And some brands have marketed their bindings that meet the 13992 standard as "DIN Certified" or "TUV Certified." And other brands haven't chased either certification, but do tout certain features as making their bindings "more safe." That's confusing for everyday skiers. In this piece, if a binding meets the 9462 Alpine standard, it earns top marks for "Safety/Release". Bindings with an adjustable lateral release value in the toe score slightly higher than bindings without, but not as high as bindings with 9462 Alpine ratings. Once you leave the world of ISO 9462 Alpine release testing, it's the Wild West, so don't blame your tech binding if you spiral your tib/fib under a downed tree.

Non-nerds skip to here!

Performance in this piece is based on how close to an alpine binding each option feels in terms of power transfer and elasticity. Power transfer is simply how solid the boot/binding/ski interface feels when you're skiing hard. Old tech bindings felt vague because your boot was floating on four pins that moved as your ski flexed. Newer options feel much more powerful. Elasticity is harder to gauge, and in my experience less important, since when you're touring you're generally skiing better snow than inbounds. Alpine bindings have some elasticity or "float" built in. This allows the ski/binding combination to help absorb chatter coming to your feet from the snow. Some options on this list have the same power transfer and elasticity of an inbounds binding, and some have none. Whether that's actually important to you depends on your style, what ski you put them on, and what kind of snow you ski. Elasticity and power transfer in the binding aren't as big of a deal if you're looking to drive a light ski in light snow with a light boot.

Weight is simple but important. If you're mostly doing short tours or booter sessions, weight is largely irrelevant. But the further you go, the more extra grams on your foot add up. The classic adage is that one pound on your feet slows you down as much as five extra pounds on your back would. And over the course of a long day, every gram counts. So if this is your first setup, you don't need to obsess over weight, but if safety and performance are equal, it's always a good call to go with the lighter option.

This hypothetical binding would max out all three values and revolutionize skiing

There’s an argument to be made that we should cover reliability or durability as well, but it’s very hard to come up with real information on that without relying on anecdotal evidence. So, I’ll include a few anecdotal notes on specific bindings, but I don’t think it’s worth trying to chart.

Finally, don't take this piece as an attack on your favorite binding. If you have one of these bindings and it works well for you, that's awesome! But every skier has different priorities, and the goal of this article is to help people figure out which bindings meet their specific priorities the best.

All weights averaged to the nearest 50 grams for simplicity. All weights reflect one foot’s worth of binding. All weights are either from my own scale, or from Skimo Co, my favorite website to nerd out on.

The charts scale in relation to their respective categories, not to some overarching ideal, so a binding in the "Alternatives" category is being graded against the other alternatives, not against a newer pin binding.

Unconventional Alternatives:

I think that you should buy modern tech bindings. But other options exist, and if I don’t cover them, someone will get ornery in the comments.

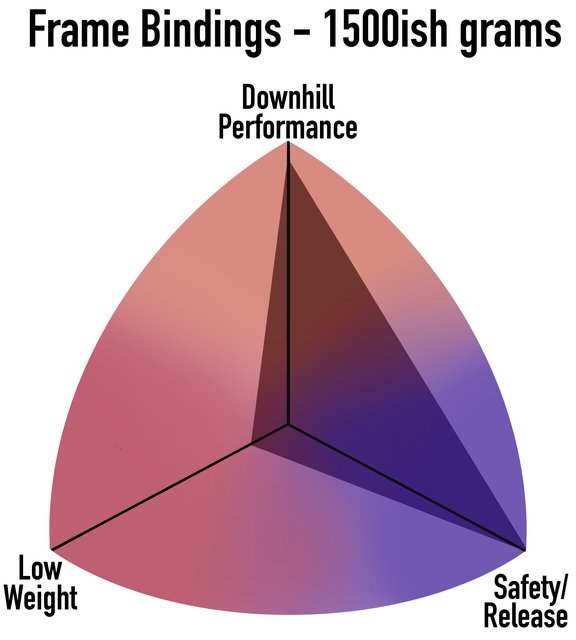

Frame Bindings - 1500ish grams

In the good old days most of us used frame bindings and they sorta sucked. They ski just like an alpine binding (with a slightly higher stack), and have the same release characteristics but they’re heavy and inefficient. I used Salomon/Atomic Guardians as an example because they’re pretty ubiquitous. Frame bindings are fine to start out on. They will get you up a hill. I fell in love with human powered skiing on frames. And they ski great inbounds, and will work with just about any boot. So if you want to start out on them, that’s great. Please don’t pay more than $60 for a pair of frame bindings though. You’ll outgrow them soon and want more.

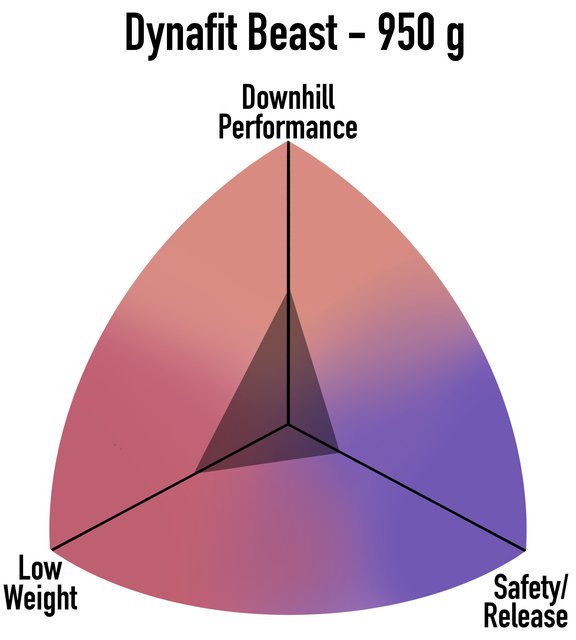

Dynafit Beast - 950 g

The Dynafit Beast was the first binding to promise to deliver downhill performance and safety with the efficiency of a pin binding. It didn’t deliver. They’re heavy. They break a lot. They don’t ski that well. They don’t have a flat mode. They require modifying your boot. They’re not any safer than other pins. Dynafit stopped selling these for a reason. Don’t buy a used pair, they’re not worth drilling holes in your skis for.

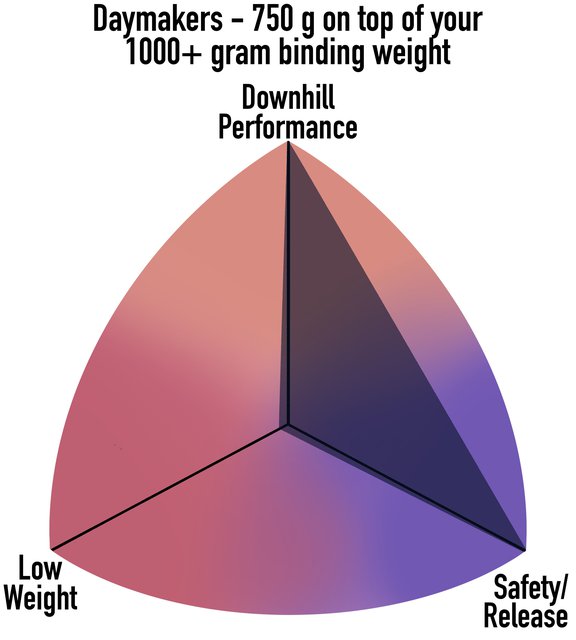

Daymakers - 750 g on top of your 1000+ gram binding weight

Daymakers are…contentious. They allow you to walk uphill in your alpine boots, on your alpine skis with alpine bindings, and ski back down. That’s nice. I understand why people buy them. Personally, I think they’re a bad investment. $360 is a lot of money to pay for something that takes up a bunch of space in your pack, adds a ton of stack height on the up, isn’t that efficient, and can’t really grow with you as you progress as a backcountry skier. A Cast Freetour kit costs $30 less than Daymakers, integrates with the Pivots many of us already have, and works so much better. Daymakers make sense for some people, I’m just not convinced that they make sense for many people.

Wrap Up

I’m not sure that anyone should buy any of these options in 2022. That's not an attack on the people that designed these bindings, or an attack on the people that like to ski on them. But there are alternatives on the market that are better in every way.

Tour-ready Bindings with Alpine Release Characteristics

This is the field that’s seen the most innovation in recent years. These bindings all let you skin uphill with the efficiency of a pin binding, and come back down with the safety and security of an alpine binding.

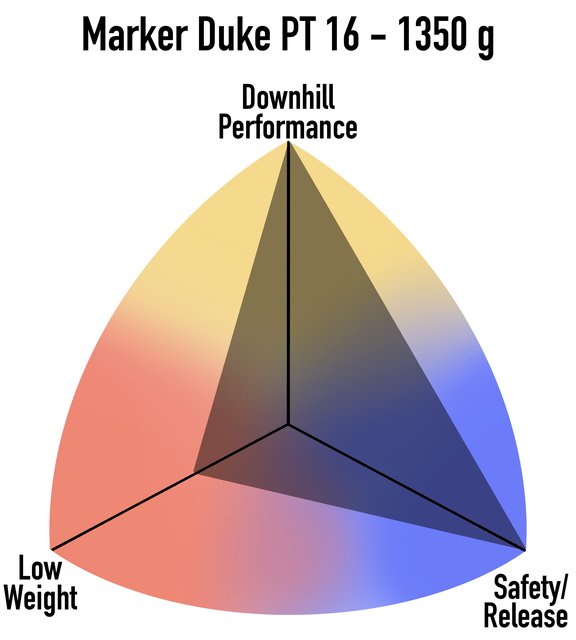

Marker Duke PT 16 - 1350 g

This is the newest player on the market. They’re available in a 16 DIN version, which is cool if you think you need that. I don’t personally have time on these, they seem great, for the right person. They’re really heavy. You can remove the toe on the way up, which makes your skis lighter, but you’re still carrying that weight in your pack. And don’t forget that toe at home, or drop it on the way up, or you’ll have a bad day. This is the only binding on this list I haven't gotten to ski yet. So all my info is second hand. I'd love to try a pair though!

If I was looking for a precisely 50/50 inbounds/touring binding, I’d probably go Duke PT.

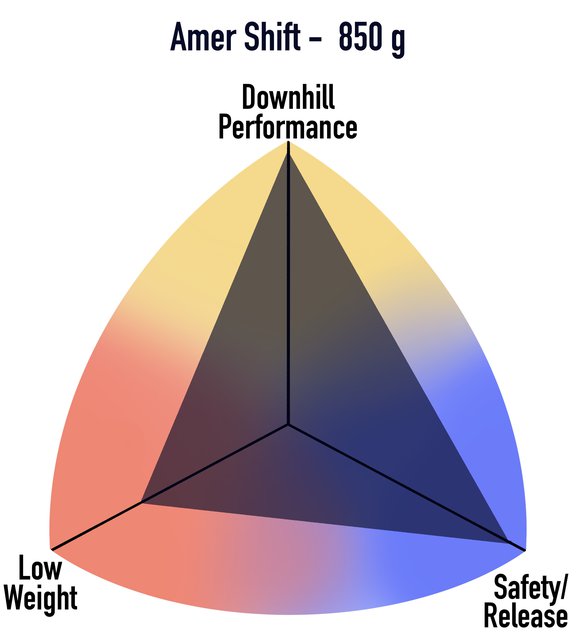

Amer Shift - 850 g

Shift is the lightest binding in this class, and the quickest to transition. It has its quirks, it’s a little complicated to adjust the AFD and forward pressure, and the brakes do have a tendency to pop down on occasion. They also only have one climbing riser, that’s a little low for many skin tracks. Still, it’s light, it skis like an actual inbounds binding, and it releases like one too.

If I was looking for a binding in this class and planned to spend more than 50% of my time walking uphill instead of riding lifts, this would be my choice.

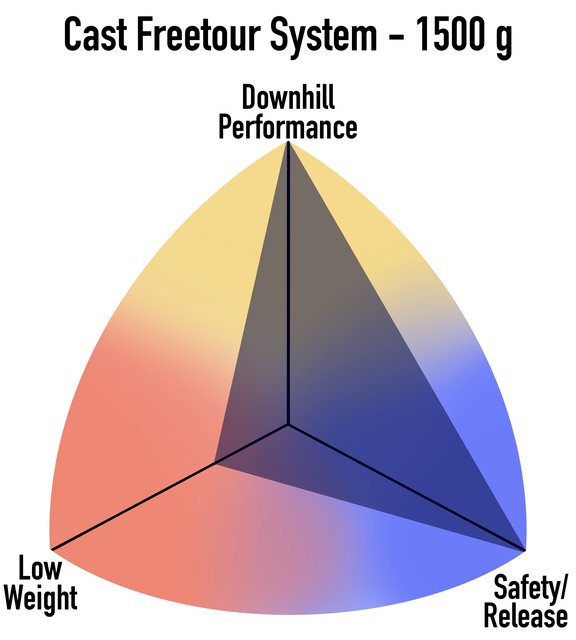

Cast Freetour System - 1500 g

Cast is the OG in this class, they’ve been doing this forever, and have a lot going for them. They ski like a Pivot because they are a Pivot. If that matters to you, this is your binding. They also have the best climbing risers in this class. They’re a little bit of a pain to transition sometimes, and like the Duke, you need to remember to pack your alpine toes.

If I was looking for a binding that I’d mostly ski inbounds, but wanted to walk on occasionally, this is the easy choice. Similarly, if I was a pro skier, risking life and limb in the backcountry, I’d drill holes for these in my skis. No one should be surprised that their team is stacked.

Pin Bindings

This is where things get complicated and we have a tendency to run into a battle of marketing vs. actual statistics. I’m lumping Kingpins and Techtons into this class because they deserve to be here. They do not have true Alpine release characteristics, and thus I think it’s hard to say that they’re any “safer” than the other bindings in this class. If you ski them consistently inbounds there’s a higher chance that you’ll break the binding, or your body, than if you were skiing a Shift, Duke, or Cast.

Some of the bindings in this class meet the DIN ISO 13992:2007 rating. That’s not the same release rating as the alpine rated bindings. It’s a rating for touring bindings. Some people put more stock in bindings that meet this standard. They use it as a justification to ski those bindings hard inbounds. A Kingpin toe does not release like a Pivot toe, so I don’t put any extra stock in bindings in this class meeting that cert. Sammy Carlson skis Kingpins with the toes locked out. That’s cool. How many of us actually ski like him though?

Anecdotally, it seems like there may be some slight safety benefits to the lateral release toe found in the Vipec and Tecton, but it’s hard to say conclusively without more scientific testing.

In this class, there are two distinct subclasses: bindings that weigh more than 500g and bindings that weigh less than 500g. So why not break these into two separate classes? Well. Some of the sub-500g bindings ski nearly as well (and are probably about as as "safe") as the much heavier ones, so they might as well all compete. That said, for me personally, when a binding is pushing 6-700 grams, I find it very, very hard not to be tempted by a Shift or Cast setup since those bindings do offer a big leap in safety and downhill performance, at a small weight penalty.

To put it simply, a Kingpin skis and releases more like an ATK Freeraider than it does an Alpine binding, but its weight is much closer to that of a Shift. So why choose it? (Risers, the answer might just be it has better risers than the Shift, safety be damned.)

Marker Kingpin - 800g

The Marker Kingpin is the original in this class. Its near-alpine power transfer characteristics set it apart when it was introduced almost eight years ago, and it’s still a good choice. That said, it’s the heaviest binding in this class, and doesn’t have any real bump in safety or performance to justify that. And for 50 grams more you could be skiing a Shift that has actual alpine release characteristics. I would recommend these to anyone on a budget, but beware, some generations had recalls and warranty issues, so if you’re buying used, do your homework.

Marker Kingpin M-Werks - 650g

Marker updated the Kingpin and shed about 150 grams when they came out with the M-Werks version. It skis like a Kingpin, weighs less, and has a fancier looking paint job. It also has slightly improved ergonomics. There’s no reason not to buy the Kingpin M-Werks, but, unless you’re getting a screaming deal, I’d be hard pressed to recommend it over some of the other options on this list either. It’s a good binding, it does its job, and looks good doing it. But it’s not the be-all, end-all of this class. At this weight, personally, I’d still go Shift for the small weight gain and big release safety gain.

Fritschi Tecton - 700 g

The Tecton is Fritschi’s answer to the Kingpin. It’s a cool binding, but one that it can be hard to find a niche for. The lateral release in the toe means it’s hypothetically safer than the Kingpin, but that’s challenging to quantify. Ultimately, I’d have a hard time not casting sidelong glances at the Shift or Cast if I was skiing Tectons. It is probably the most alpine feeling binding on this list though, in terms of both power transfer and elasticity. It's noticeably more elastic in the toe than the Kingpin.

Fritschi Vipec - 600 g

The Vipec is another interesting option. It’s really easy to use, and the ability to transition the heel from touring mode to skiing mode and back again without taking the toe out is handy. And it has the same lateral release in the toe as the Tecton. This was my top recommendation for years, and it’s still a great binding, but in recent years, lighter options that transfer power to the ski just as well have upstaged it. It’s worth noting though, that some skiers really prefer the Vipec and Tecton for their more alpine-feeling elasticity. That’s independent from their power transfer, they just offer a “damper” feeling ride. Some people really enjoy this, I find that I don’t notice it much on the down, and I end up with a vague feeling on the skin track that I don’t like. If this elasticity is important to you though, check out these bindings. It’s noticeable.

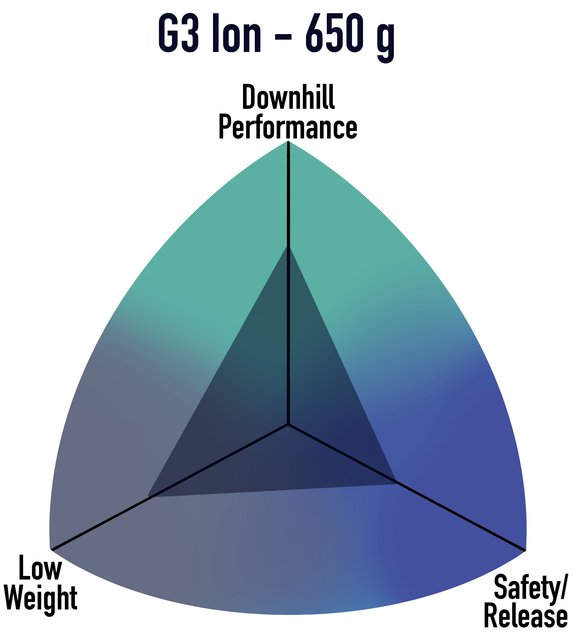

G3 Ion - 650 g

I find it challenging to advocate for this binding. It’s a fine binding, but at this weight it doesn’t bring anything interesting to the table. It doesn’t have the lateral toe release of the Vipec, or the power transfer of a Kingpin or Tecton. So why carry the extra grams around? In addition, I’ve personally broken, and seen more friends break Ions than any other binding. It’s not even close. So I don’t ski these anymore. If they work for you, great!

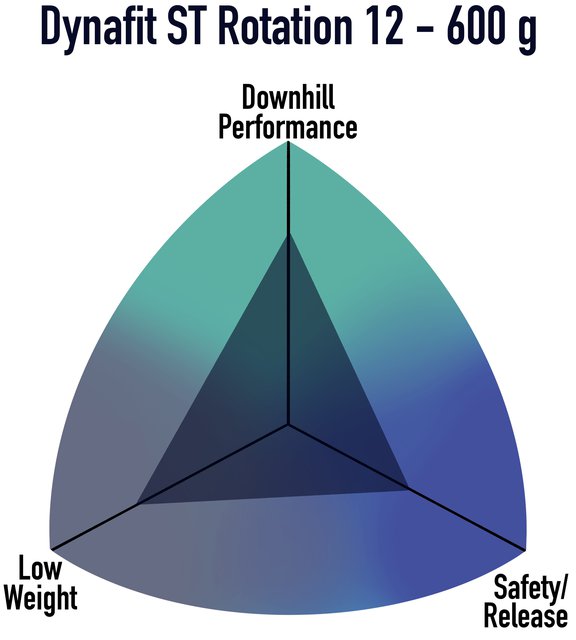

Dynafit ST Rotation 12 - 600 g

Dynafit has pared things back from the days of the Beast, and the ST Rotation is the result. The rotating toe helps them achieve the TUV touring standard, so that’s a plus. They don’t feel as “alpine-y” as the Kingpin or Tecton though, so if that’s important to you, look elsewhere. At this weight, I can’t help being tempted by the heavier bindings in the category above, or the lighter bindings detailed below.

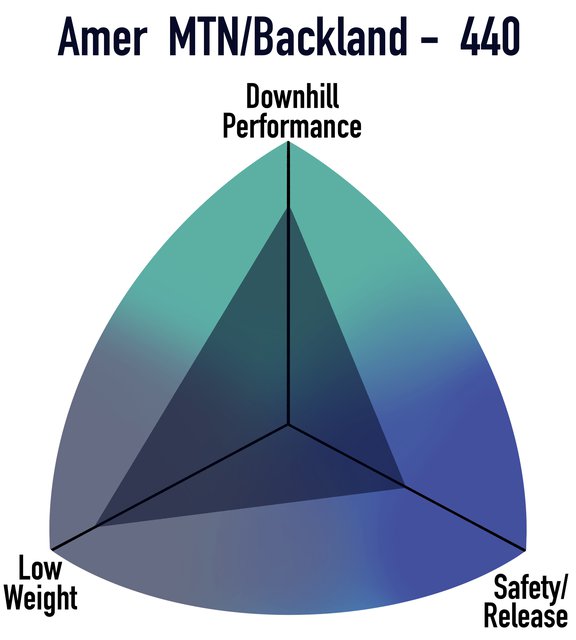

Salomon/Atomic/Armada MTN/Backland - 440 g

This binding is odd. It’s better than it should be. But first, the bad. It only has three release values, “Men, Women, and Experts.” That’s some shit if I’ve ever seen it. But it also sort of correlates with my own mentality that specific numbers on tech bindings are nearly irrelevant, just find a release range that seems like it works for your unique combination of size and stupidity. It's not like there's a DIN calculator for tech bindings after all.

Most people run an intelligent release setting that’s not too bold, tall heavy people like me run things a little higher, and then pros just crank that shit all the way up. So, I hate gendered release values, but also, I’m happy skiing the middle release value for MTN’s which just happens to be “Men.” And my partner is very happy in the “Women” setting.

This binding doesn’t have an alpine heel or any features that would be touted as making it transfer power better, but I’ve found that the brake lever acts as a de facto heel platform, and this binding actually feels shockingly similar to a Kingpin in terms of power transfer. It’s not quite as strong, but it’s closer than it has any right to be. It also uses a U Spring design, which some brands are really pushing back against, since it's more likely to wear and provide less consistent releases. (Not that I'd expect a spring setting called "Man" to release consistently anyway...)

It’s also worth noting that the MTN heel doesn’t have any elasticity. The other bindings in this class do. That means it’s more likely to prerelease when you’re flexing the ski hard, and hypothetically doesn’t have quite as consistent of a release. In practice I’ve never had a problem, but your experience may vary.

So no, this is not the binding for days where you think you'll be ejecting a lot, but for everything else, it’s way better than it should be. And it can often be had for cheap.

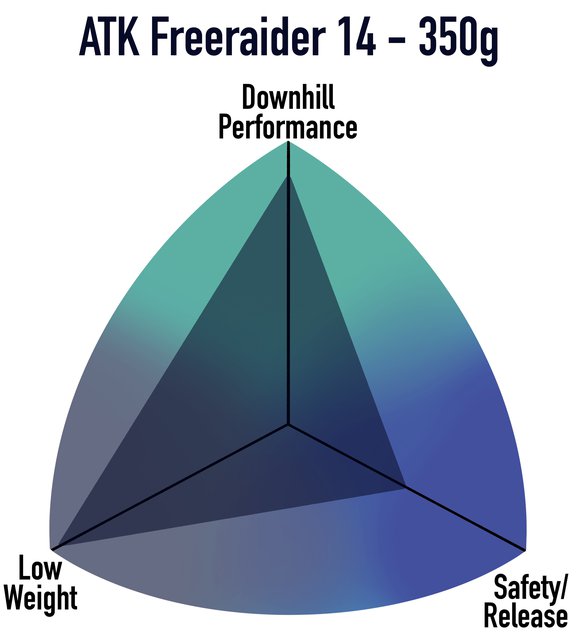

ATK Freeraider 14 - 350g

This binding is really good, so it makes sense that everyone and their mom is rebranding it and selling it. It’s the lightest binding in this class, it’s less than half the weight of the original Kingpin, and thanks to its “Freeride Spacer” it feels about the same in terms of power transfer. It’s really, really easy to use. The climbing risers work well and are easy to flip with a pole. I can’t say enough good things about Freeraiders. They weigh the right amount, it would be hard to argue that they’re significantly less safe than other pin bindings, and they ski really well. As far as downsides, they don’t have the safety of a Shift, or maybe even a Vipec, and the brakes are a little insubstantial. They also don't have the toe elasticity of the Fritschi bindings, but personally I find that I overpower touring boots long before I notice any "harshness" in the toe of my bindings. But that’s a small price to pay for 350g bindings that ski like 800g ones. This is my top choice in this class, by a large margin.

Lighter Options

Yes, there are so many exciting bindings not on this list. That’s because this is a website for freestyle skiers. And while you can hypothetically spin and jib your way down the mountain on lighter options, it’s probably not the best call. But, if you get hooked on touring and want to get weird, there are plenty of great websites out there who will be happy to help you shave grams.

Conclusion

Backcountry skiing is really fun, regardless of what bindings you’re on. But there are a lot of options on the market and it can be hard to figure out what you specifically should be looking for, so hopefully this provides a good starting place to help you narrow down your options.

Comments