Andrew Nyberg, the doctor who wrote the account below, in Thokla Pass. Andrew Nyberg Photo

Andrew Nyberg, the doctor who wrote the account below, in Thokla Pass. Andrew Nyberg Photo

Andrew Nyberg is an ER doctor from Park City, Utah and a Wilderness Medicine Fellow at the University of Utah. He currently volunteers as a doctor at the Himalayan Rescue Association (HRA) in Pheriche, Nepal, which is the closest medical clinic to Everest Base Camp (EBC). After the earthquake, he and the other three doctors at the HRA clinic treated 73 injured climbers, porters and Sherpas as they were being transported away from base camp. Andrew's brother reached out to us today to share his story. These words are Andrew's and give one powerful perspective of the tragic events that unfolded this weekend.

25 April 2015

Pheriche from above. Andrew Nyberg Photo

Pheriche from above. Andrew Nyberg Photo

I have only ever been in one earthquake in my life. When I was biking across America with Ride For World Heath, we experienced a small earthquake in Dateland, Arizona. Earthquakes are described as a shaking, however I think that is a wrong description. Shaking implies that things go back and forth in an almost rhythmic pattern. In the two earthquakes I’ve now experienced, it felt more like floating on turbulent water. It’s not rhythmic; it’s random. And for those not used to earthquakes, it takes a few moments to realize that you’re in the middle of one. Right as Tan and I were looking at each other, saying “we better get out of here”, Gobi was already outside pounding on the windows for us to get out. Renee, Katie, and Reuben were still sitting in our common room, trying to figure out what was going on when they saw Tan, my patient and I bolt for the door, and they soon followed.

The quake only lasted a few moments, and to my unaccustomed body it actually was pretty underwhelming, until I had the chance to see the changes to the world around me. Pheriche is a small town with approximately a dozen lodges that cater to trekkers and climbers, with a few private buildings. After the earthquake, only two of the lodges remained without any damage. The style of building common in the Kumbu region is to build with shaped stones, usually without mortar. Many of the walls of these buildings had weaknesses that caused them to fall after the earthquake. The HRA clinic lost the wall on the Southeast corner, where the bathroom, and the room where Jeet, our cook, slept.

In spite of the tremendous damage to the town, there was only one casualty, one of the Nepali women in town was hit in the head with a stone and had a small laceration to her scalp, which I stapled closed.

Dingoche, the large neighbor town of Pheriche. Andrew Nyberg Photo

Dingoche, the large neighbor town of Pheriche. Andrew Nyberg Photo

We then entered the period that was effectively the calm before the storm. It was lucky the earthquake occurred in the middle of the day, when most of the trekkers were out on the trails. Knowing the amount of damage that Pheriche sustained, we expected bad things from Dingoche, our neighbor town on, which was larger. For the next several hours we kept an eye on the hill, expecting to see casualties coming from next door, but none ever came.

Earlier in the season we had set up a new communication system that allowed us to talk with Everest ER. We kept sending out messages to our neighbors to the North but never heard a response. We were in the dark about their fate until Gobi was able to reach HRA’s headquarters in Kathmandu by satellite phone. That was when we first heard that there was massive damage to Kathmandu. We also learned that while the staff of Everest ER was safe, their tents were completely destroyed. At the time, they were estimating two deaths, ten critically wounded and twenty less critically wounded.

At 3pm, three hours after the initial quake we were rocked by a large aftershock that added more damage to many of the structures in town. With the threat of continuing earthquakes, we decided to sleep in the sunroom, which we supposed would be safer than sleeping in our rooms in the clinic. The trekkers in town mostly crowded into the Panorama Lodge, one of the few intact structures in town.

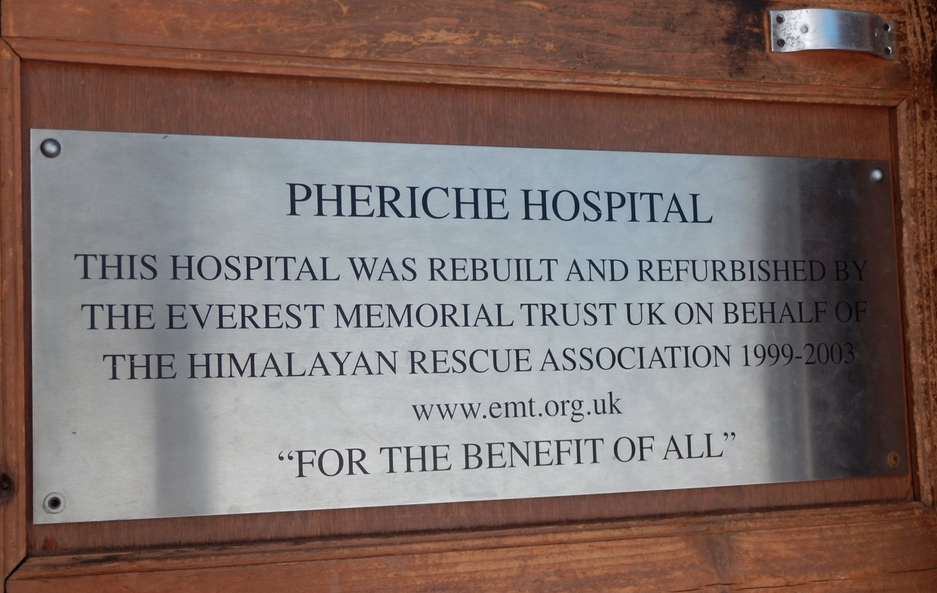

Inscription at Pheriche Hospital. Andrew Nyberg Photo

Inscription at Pheriche Hospital. Andrew Nyberg Photo

Although we were on continuous alert for the possibility of patients arriving, they never did. April 25 was not a good day for an earthquake in the Khumbu, as the day was overcast, cold, and snowy. Helicopters were not flying. We knew our friends were in a bad way, and we suspected that our lives would get busy in the near future, but were unable to predict when.

But with darkness falling, there was little to do but fall asleep. I was just about there when Tan woke me, saying, “Andy, Andy…” “What?” “We have a patient”.

And so at 9pm our first patient arrived from Everest. He was a young Nepali who had been thrown several feet by the blast of air the preceded the avalanche. The patient’s friend had gotten to him right away, put him on a horse, and then took the next 9 hours to get him from EBC to Pheriche.

It is important to know that when a large avalanche forms, it displaces all the air in front of it, so before being struck by the avalanche, EBC was struck by a huge gust of wind. Several people who were there told me that this wind did a tremendous amount of damage when it hit the camp.

We had gone from care with a scalpel to care with a saber: concentrating on vital signs, checking airway, breathing, and circulation, identifying injuries, and looking for obvious threats to life.

The patient was complaining of right-sided pain in his ribs, his upper abdomen and his thigh. Hearing decreased breath sounds, I worried that this man’s rib fractures had caused a pneumothorax. An ultrasound of the lungs confirmed my suspicions. He also had rights sided flank pain, and a sample of urine contained blood and protein. I was concerned he may have damaged his kidney, or developed rhabdomyolysis, a dangerous breakdown of muscle tissue. Since his oxygen saturation was good, I started him on oxygen to help decrease the pneumothorax, and started IV fluids. A FAST ultrasound exam was negative, and I even ultrasounded his right femur with no sign of fracture. I tell you these medical details, not because I assume you are interested in the medical details, but to juxtapose the time and care I was able to give this patient compared with what was to come.

A second patient followed closely behind the first, with a hand injury. Renee treated him, and he was discharged. Although we were told that more patients were coming, we didn’t see anything more that night. We continued to monitor our one patient, and got a good, if cold, night’s sleep.

April 26, 2015

Patient room at HRA. Andrew Nyberg Photo

Patient room at HRA. Andrew Nyberg Photo

I woke up at 5:45 when a FishTail Eurocopter flying by the Pheriche valley on its way to EBC. Aroused by this inordinately early flight, I got up to check on my patient. He was doing well, but a repeat FAST exam showed a full bladder, after he was unable to urinate, I became worried that he was obstructed for some reason, and all the IV fluids I was poring into him would eventually need to come out. As I was preparing to pass a Foley catheter through his urethra to drain his bladder, I got word that we were getting patients.

The FishTail pilot arrived with the two most critical patients, one with a head injury and the other with substantial orthopedic injuries. As the pilot unloaded the patients, he told Reuben, “I’ll be bringing you about 51 more patients.” For two hours, this one pilot was the only helicopter flying in the Khumbu. Clouds had socked in the Lukla airport, and none of the other helicopters could take off.

As more patients arrived, I took over the two clinic rooms, seeing four critical patients, including my patient from the night before. Katie was stationed at the room we use for research, and spent a large amount of time with one patient who was clearly our most critically injured. Renee transformed the sun room, which we had been sleeping in a short while before, into a third clinical space, and was able to get six patients on the floor in the room we normally use for our daily 3pm Altitude talks.

View of Pheriche. Andrew Nyberg Photo

View of Pheriche. Andrew Nyberg Photo

On one of the early helicopters, Meg Walmsley, an Australian anesthetist working at Everest ER, flew down to help us with the patients. She had been in the Everest ER tent treating a patient when it was blown down. The earthquake had set off an avalanche, which we all knew. What Meg told us, however was that the avalanche that took our EBC came from the nearby mountain Pumori, not from Everest, as we had all suspected. Meg lost all of her personal effects, and the Everest ER tent had been destroyed. She had spent all night treating patients at EBC, but then valiantly offered to come down to Pheriche to help us continue our care. Initially she helped Renee in the sunroom, but as more patients arrived with no concrete plans to evacuate them in site, we took over the dining room of the Panorama lodge, and Meg was tasked with caring for all the new cases that were being brought there.

The situation was quickly becoming a mass casualty incident, or what the American College of Emergency Medicine would call a medical disaster, which they describe as a situation “when the destructive effects of natural or manmade forces overwhelm the ability of a given area or community to meet the demand for health care.” In spite of the time and resources I could devote to my patient last night, we had gone from care with a scalpel to care with a saber: concentrating on vital signs, checking airway, breathing, and circulation, identifying injuries, and looking for obvious threats to life.

One of the large miracles of the day was how people kept showing up with offers to volunteer. We were in desperate need of doctors, nurses, and others with clinical knowledge that could triage and treat the patients that kept poring into our small town. But there were many people with no medical knowledge who also became incredibly important, working as scribes, taking records of patient names, and helping carry the injured. Early on we developed a system of using wide pieces of tape with markers to identify names, vital signs, and injuries on patients. This would help us quickly identify our sickest patients, and if we could evacuate the patients, this would help care providers down the road.

In spite of the bad weather over Lukla, Gobi had worked his considerable persuasive magic, and we were being told of a plan to get a Mi-17, an old Russian military helicopter, to fly to Pheriche, where it could take approximately 15 patients at a time. We now had the task of identifying which 15 patients were the most critically injured to assure they were on the first flight out. The weather patterns in the Khumbu are erratic, and you are never sure if a helicopter will make it, or if that helicopter was able to return, so it was important we get our worst patients out if an when we got the opportunity.

This is where one of our volunteers became a real hero. She and I went around, from the clinic, to the sunroom, to the Panorama, and talked with Renee, Katie, Meg, and the other clinicians to identify the patients that were in greatest need. We placed a sticker with a giant ‘E’ on each coat or sleeping bag, so it would be obvious to volunteers which patients needed to move. When helicopters land in Pheriche they don’t turn off their engines, this means things have to move quickly, and we could have no delays. Getting these patients down was the best way to save their lives.

The news concerning evacuation kept changing, and at first it sounded like the weather was too bad for any helicopter to lift. My biggest worry was that we would not be able to evacuate our patients, and would have to keep them over night. I was working with some wonderful volunteers, but at some point they would have to move on. How long could I expect Pemba to allow us take over his lodge and keep patients there? What if we had dozens of patients that needed to stay the night? How could we keep the critically injured alive when we didn’t have blood products?

A helicopter flies into Pheriche in early April. Andrew Nyberg Photo

A helicopter flies into Pheriche in early April. Andrew Nyberg Photo

At one point Reuben came around with a Chipati (think of a tortilla) with nutella inside, he said “Andy, you’ve gotta keep your strength up, I can’t have my doctors hitting a wall”. I thought to myself, is it lunchtime already? Only later did I realize that I hadn’t even had breakfast.

At some point in the morning, Ken Zafren arrived. Ken is an emergency physician at Stanford and Alaska Native. In the world of wilderness medicine he is a legend, and as the physician who recruits all the HRA volunteers, he is very heavily involved with the HRA. Although he had experienced the earthquake, and was aware that there had been an avalanche at Everest, he was completely unprepared for the amount of damage that had occurred in Pheriche (something we would hear frequently), and was surprised to walk into a mass casualty incident. His wisdom and experience were incredibly useful.

Reuben then came back and informed me, “We think the Mi-17 will be landing in an hour, get ready with your 15 sickest patients.” But then, before we knew it, two Eurocopters landed, and were headed back to Lukla. They had room to take four patients. We unloaded our four worst cases, Katie’s head injury patient, my orthopedic patient, and two other patients with head injuries that weren’t looking very good.

We had identified one other critical patient, so my list of 15 had dropped to 12. I started having volunteers transport them down to the “helicopter beach”, where they could wait in anticipation of the Mi-17.

A MI-17 heli. Defense Industry Daily Photo

A MI-17 heli. Defense Industry Daily Photo

The Mi-17 arrived as I was coordinating transportation of the critical patients. After I had gotten them all carried down to where the helicopter was, I headed there myself. To my utter chagrin, I saw the Mi-17 lifting off and five or six of our sickest patients were still on the ground. I then realized that several of the “walking wounded”, injured patients who were not critically ill, and could mostly still walk, had taken the opportunity to evacuate themselves by getting on the Mi-17.

Katie was caring for some of the patients, and Reuben, Gobi, and Tan were trying to coordinate helicopters and patients. I yelled at the crowd to “listen up”. I told them that ABSOLUTELY no one could get on a helicopter unless Katie had given them permission. The lack of leadership had lost us an opportunity to evacuate some of or sickest patients, and I needed to make sure that the HRA continued to keep stay in control of the situation, before someone else realized the power vacuum, and started trying to run the incident themselves.

With Katie in firm control of how patients were getting evacuated, I was able to return to the HRA and Panorama. It was clear that with our most critically injured patients being evacuated, we were shifting into a new phase. Now, with helicopters arriving to evacuate patients, the focus shifted from prioritizing acuity rather, and less stabilization. Also, the HRA staff began assuming leadership roles, whereas the direct triage and stabilization of patients fell to the nurses and physicians who had volunteered to help.

Andrew Nyberg poses in front of a grouping of prayer flags. Andrew Nyberg Photo

Andrew Nyberg poses in front of a grouping of prayer flags. Andrew Nyberg Photo

I returned to the Panorama lodge, where most of the remaining patients were, and announced we were changing things. Now any patients needing helicopter evacuation would go to one wall, while those who could potentially walk out or ride a horse on the other. We were lucky to have the Mi-17 and the Eurocopters available to evacuate patients, however I wanted to make sure all those who needed it got out, in case we lost those resources.

But in the end, that concern wasn’t warranted. All the patients from Everest had been brought to Pheriche. We were able to evacuate them to the airport in Lukla using three trips with the Mi-17, and about 10 trips with Eurocopters. When the last of the patients was loaded onto the Mi-17 and that beautifully large military helicopter took off over the Pheriche Valley, I looked down at my watch. We had a lot of people to thank.

Most of the volunteers, and almost everyone else in town was standing on the “beach”, which is really the main hiking trail through town. They were there to watch the helicopters take off. I called their attention. I told them, “In less than five hours, we treated and evacuated approximately 40 patients. Those of us at the Himalayan Rescue Association are volunteering our time to be out here. Today you are all volunteers of the HRA with us. Thank you for your help; there is no way we could have done this without you.”

Later Katie, Renee, Reuben, and I took a walk, and we figured out that I had grossly underestimated the miracle we pulled off. The first patient arrived at 6:40 am. The last patients were leaving just before noon. But we hadn’t seen 40 patients; we had seen 73.

A medical evac form Pheriche in early April, not this weekend. Andrew Nyberg Photo

A medical evac form Pheriche in early April, not this weekend. Andrew Nyberg Photo

After the patients had gone, the HRA staff, along with Meg Walmsley and Ken Zafren, pulled chairs around our entrance room, and opened our last bottle of Coke. Like a bottle of Dom Perignon, we had been saving it for a special occasion, and this seemed the perfect time.

At approximately 1pm, 25 hours after the original quake, a second aftershock shook us out of our comfort. After the hectic events of the morning, it was hard to get back to life as normal. A group of people showed up for our 3pm daily altitude talk, and I only noticed it because I happened to walk by at 3:05.

April 27, 2015

Today became an odd contrast to yesterday. Yesterday we saw nearly 80 patients in a single day; today Pheriche was like a ghost town. Yesterday we were fighting for life; today we bore witness to the dead.

The helicopters were evacuating climbers from Camp 1 and Camp 2, and then were evacuating climbers to Pheriche, before heading down to Lukla. Today the body bags also came down. As a physician at the HRA, you become good friends with many of the Everest climbers, and today was our opportunity to see some of them again. It was a time to rejoice for the lives that made it, and a time to mourn for those who died.

Time will tell where this story goes. Perhaps, as I stated in the beginning, God has more of a role for me to play in this disaster.

It is also a time of uncertainty for Katie, Reuben, Renee, and myself. The trekkers are all leaving, and in a few days there won’t be any more trekkers or climbers. With most of the lodges closing, many of the Nepali workers are also leaving.

In a time when organizations all over the world are mobilizing to send aid to Nepal, we are uncertain of our continuing role in this disaster. On the one hand, with our proximity to all this suffering, it would make sense for us to try and dive in, and help wherever we can. On the other hand, after what we’ve been through, after what I’ve been through, I’m not sure how I will handle what awaits in Kathmandu.

Our thoughts are now more than ever directed towards home.

Time will tell where this story goes. Perhaps, as I stated in the beginning, God has more of a role for me to play in this disaster.

Stephanie Nitsch

April 27th, 2015

This gave me chills. Kudos to Andrew and his team for managing a catastrophic event with poise and clarity. Thoughts go out to those who perished at the unpredictable hands of the mountains.

DIGITALDEATH

April 27th, 2015

ya but what is his fucking handle in the forums?

digitaldeath wants to know

Olaus Linn

April 27th, 2015

Amazing, hair-raising story. Andy: huge thank-you from all of us to you, your team, and all the people who helped out for the amazing job you guys did. You saved a bunch of lives.

Todd Jones

May 1st, 2015

Andrew, you are a hero. I can’t imagine going through this. Thank you so much for sharing this here.